Link for annotated oral history segment:

https://ohms.uky.edu/meta.php?id=100236&m=1

Link for annotated oral history segment:

https://ohms.uky.edu/meta.php?id=100236&m=1

After sketching out the storyboard for my project, I then went back to revise and take a second look at the storyboard. When I took a second look at my storyboard, I made some changes to order the information was presented and which sources I wanted to present in each section. From here I made notes on what information and major themes I wanted to highlight in each section of my project.

The next major step was beginning to transfer the ideas I had on paper over to Omeka. I had previously uploaded all of the items I personally owned that would be used in my project. What I did at this point was find, save to my computer, and upload to Omeka all of the remaining items that will be part of my project. I have so far uploaded and filled in the metadata for all of the items that will be part of my project. I have also created all of the exhibit pages that will make up my project and uploaded all of the items onto their corresponding exhibit pages.

The biggest challenge I am facing right now is transferring the design I have on paper for the way my project should look, to Omeka. I am currently figuring out how to use Omeka to make my project look the way that I want it to look. The other challenge I am facing right now is figuring out how to create the interactive timeline that I want to include in my project. I in the process of learning how I would create a feature like this and add it to my project.

The next steps in my project involve writing the descriptive captions for each of the items in my project and writing the text for each of the different sections of my exhibit. This is a crucial step in my final project that will provide the context for the entire project.

My digital history project will examine the story of one immigrant group, the Carpatho-Rusyns in the United States, and the process of Americanization among this group and their descendants. This will be accomplished by analyzing one of the major institutions established by Carptho-Rusyns in the United States, the Byzantine Catholic Church (also known as the Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church). Examining the establishment and evolution of the Byzantine Catholic Church over time, provides an insight into how the Carpatho-Rusyns were Americanized. The project will organized in a narrative style that will tell the story of how the Byzantine Catholic Church was established in the United States and how it adapted over time to reflect the values and concerns of its members.

There are a few different history questions that this project will address. To begin the project, I will first provide a brief background of the religious characteristics of the Carptho-Rusyns in their European homeland. Then I will examine what the religious situation was like in the United States when the Carpatho-Rusyns began arriving in the late nineteenth century. From there I will look at why these immigrants felt the need to established their own unique church in the United States. The project will then progress to examine what were some of the changes that the Byzantine Catholic Church made as its members began to Americanize. Finally, the project will end by reflecting on how changes in the Byzantine Catholic Church reflect the larger process of Americanization among Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants and their descendants. This reflects the major question that this project looks to answer, how does the establishment and evolution of the Byzantine Catholic Church, in the twentieth century, reflect the assimilation process of Carptho-Rusyn immigrants in the United States.

The content for the project will come from a variety of different sources. Most of the primary sources will consist of photos and documents of the Byzantine Catholic Church and its members. These items will consist of personal family photos depicting events such as marriages and First Holy Communions and religious books and texts, all of which reflect the importance of the Byzantine Catholic Church in the lives of Carpatho-Rusyns. These will help to create a more personal narrative by placing one family in the context of the Byzantine Catholic Church. The project will also include photos and documents gathered from other cultural organizations that specifically focus on Carptho-Rusyns. These sources will help to provide the background to the important events that occurred in the evolution of the Byzantine Catholic Church.

This project will be created using Omeka. Through Omeka I will create a digital exhibit that user can navigate through in chronological order. The information will be organized into different exhibit pages that will follow the establishment and evolution of the Byzantine Catholic Church in the United States from the late nineteenth century up to the present day. The items displayed in the project will all be digitized by either being photographed or scanned and then uploaded onto Omeka. Finally, I will also be using Leaflet to create two different maps to provide context to my project. One map will be the location of the Carptho-Rusyn homeland in Europe, and the other map will show the locations of Byzantine Catholic churches in the United States.

There are two different target audience for this project . The primary audience for my project will be members of what is called either the Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church or the Ruthenian Byzantine Catholic Church that are interested in learning more about their family history and heritage. These individuals will be located mostly in the Northeastern United States, be about 40-60 years old, and will have a high interest in genealogy and learning more about their ancestors. The secondary audience of my project would be scholars interested in the development of religious communities in the United States. This group would consist of scholars that study the development of different religious communities in the United States and how distinct religious communities were created and developed. The Byzantine Catholic Church is an example of the type of unique religious community that these type of scholars would be interested in.

Persona 1:

Name: Gary Kachmar

Demographic: 55; married; lives in Scranton, PA; bachelors degree in nursing; middle class

Quote: “The best surprise was finding the village my grandfather came from.”

A Day in a Life Narrative: Gary has been interested in learning about his family history since he was a child. Growing up, he was always eager to hear stories about his grandparents and great-grandparents. Gary knows the details about his ancestors’ lives in the United States, but does not know much about where they came from in Europe. All he knows is that his father told him that they were Rusyn. A recent conversation he had at work got Gary interested in learning more about his family’s European roots. After doing some research online, he discovered a few different websites that explains what a Rusyn is and where they come from. He joined a few different Facebook groups that discuss Carpatho-Rusyn ancestry and have led him to find out more about the villages where his family comes from in Central Europe.

End Goals: Gary hopes to find out more detailed information about where his ancestors came from and what their lives were like. He hopes that online research and participating in discussions forums on his Carpatho-Rusyn heritage will give him a greater insight into where his family comes from so that he can one day take a trip to Europe to see for himself the villages his ancestors are from.

Persona 2:

Name: Andrea Gerwig

Demographic: 57; married; lives in West Chester, PA; bachelors degree in chemical engineering; middle class

Descriptive Title: Chemical Engineer

Quote: “All I know about my grandfather is that he came from Austria-Hungary in 1910.”

A Day in a Life Narrative: Andrea grew up knowing very little about her family history. She remembers being told that she was Polish and Slovak but does not remember anything more than that. After the death of her mother Andrea realized that she really did not know much about her family’s history to tell her children. She began to do some research based on the very limited knowledge she had and was able to discover that she was not Slovak but instead Carpatho-Rusyn. After discovering this fact, Andrea discovered that a variety of different websites and forums that provide information about the Carptho-Rusyn people. She has begun to use these resources to learn more about her family and where they came from.

End Goals: Now that Andrea has gained a new interest in learning about her family, she wants to make sure that her children know more about her ancestors that she did at their age. She has been using various online forums to learn more about her family to create an extensive family tree to pass down to her children.

When historians work they, like any creator, are creating content for a specific audience. There is always a target demographic that every type of historian is looking to appease. A large part of the work that historians create is meant for a purely academic audience that consists of their fellow historians. It these instances they are creating scholarly content to engage with academic debates with their fellow historians. However, not all historians create content for a purely academic audience. A notable exception can be found in public historians.

As the name implies, public historians largely work with and create content for an audience consisting of the general public, meaning individuals who are not academically trained historians. As Denise Meringolo states in her book Museums, Monuments, and National Parks, “Public historians can produce original interpretations that connect scholarship and everyday life by respecting the ways in which their partners and audiences use history and by balancing professional authority against community needs.” (168) It is ultimately public historians that bring together the academic community and the general public in the projects they create. The projects that public historians create are meant to be experienced by a wide ranging audience that come from diverse demographic backgrounds. As a result, the general public has a large role in determining the types of content found in public history projects.

At all stages of creating a public history project, it is important to take into account how the general public audience will experience and interact with the project. Any public history project should be created with a goal of marketing it to a large scale audience. The project Histories of the National Mall provides a perfect example of a project created with the goal of being used by a large public audience. As stated in the project guide, “We decided that our primary users would be the 25 million tourists who visit the

Mall each year.” (8) Determining that the primary audience of the project would be anyone who came to visit the National Mall, meant that the project content had to be accessible to a large number of people in an outdoor space. The project team reflected this in the design of the project stating, “Our key strategy for making the history of the National Mall engaging for tourists was to create a website designed for hand-held devices, populated with surprising

and compelling stories and primary sources that together build a textured historical context for the space and how it has changed over time.” (4) Creating a website allows the project’s content to be viewed by the public in a way that is engaging to them while they are physically present on the National Mall. Histories of the National Mall is a prime example of the nature of the project’s audience shaped the way that the project’s content was presented to them.

Throughout the development of a project, public input can play a key role to both reinforce or change the direction of the project and the the type of content it contains. Since public history projects are created for the public, it is important that they have a say in the type of content that projects create. To be successful, a project has to peak the interest of the public and encourage them to engage with the project. In his essay “Creating a Dialogic Museum: The Chinatown History Museum Experiment,” John Kuo Wei Tchen describes how the Chinatown History Museum in New York City used interactions with their target audiences to shape the content offered in their exhibits. “Laundry workers, for example , asked why our Eight Pound Livelihood exhibition had more photographs showing laundrymen than photographs showing the work process. We learned from their comments that they would have represented laundry life in an exhibition very differently than the CHM staff had.” (310) By engaging with the audience the staff at the Chinatown History Museum were able to adapt and change the content of their exhibit to make it more meaningful for the intended audience. This is one example of using public opinion to create a public history project that has a greater meaning for its audiences.

While public history projects are created by historians with their own interpretations of history, the public audience for their project ultimately play a major role in determining the content of said project. The public historian has to create content that is engaging to the public and invites them to interact with the project. As a result, the project content has to appeal to the whatever the target demographic group the project creator has in mind when working on the project.

In conducting my research, I discovered a number of unique characteristics of the target demographic group for my project. This demographic group consists of mostly middle aged men and women from the northeastern United States, who are married, middle class, and have either a high school or bachelors level education. This demographic group has a high interest in learning about and discovering stories that are part of their family history and would have affected their ancestors. I found that as long as I can appeal to their desire to learn more about their ancestral background, I could capture their interest in my project.

There are a number of characteristics of this demographic group that I will be taking into account as a work on and create my project. This group tends to do most of their research online through a variety of different websites that are dedicated to genealogical research. Many of these websites deal with providing guidance and directing users to resources that are helpful in discovering information about different European ethnic groups that immigrated to the United States.

I also discovered that many of the people in this demographic group are part of online groups and forums that are dedicated to genealogical research and family history for specific European ethnic groups. In these groups, members will post articles about different topics, ask a variety of different questions, and post resources to help other members in their own research.

Based on the findings of my research, I will tailor my project to reflect how this group interacts with a topic similar to the one covered in my project. I will design my project to be similar to the type of informational websites that individuals in this groups visit when conducting their research. In addition, I will also use the different online forums to promote my project and get feedback from individuals as to how I can improve upon and change my project to have a more widespread appeal.

National Archives Museum: Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote Exhibit

Physical Site:

This exhibit makes the argument that American women gaining the right to vote was a long and complicated process that involved the hard work and sacrifice of many individuals over several decades. The physical design of the exhibit allows the visitor to experience first hand what were the struggles and obstacles that women had to overcome to get the right to vote by providing the opportunity to both read and hear first-hand accounts of suffragists and how they perceived their involvement. The exhibit takes a neutral stance on current political issues that involve voting choosing to present both sides of these issues.

The primary audience for this exhibit is the general public. In the exhibit space there are visitors of all ages and backgrounds. Visitors in the exhibit range from school aged children all the way to retired senior citizens.

The exhibit is primarily composed of primary source documents that includes petitions sent by suffragist organization to Congress demanding women be granted the right to vote, letters sent by suffragists to politicians, and the actual official certified copy of the 19th Amendment. All of the documents used in the exhibit relate to some aspect of the effort to secure voting rights for women in the United States. These primary source documents are supported by both written and video explanations that help to explain their significance to visitors.

The exhibit is divided into five thematic sections that each ask a question. These sections are organized to move roughly chronologically going from the late 18th century up until the present day. The five sections are: Who decides who votes?, Why did women fight for the vote?, How did women win the 19th Amendment?, What was the 19th Amendment’s impact?, and What voting rights struggles persist?. The exhibit is easy to navigate as there is only one way visitors can walk through the exhibit, ensuring that they view each of the different sections in a certain order.

The exhibit contains a few different interactive elements. One interactive consists of a game where the player has to navigate through a maze to try and get an amendment passed. Along the maze there are various roadblocks that stop the player from moving forward, these are representative of elements that can stop an amendment from advancing to become a law. The other interactive is a voting machine that the visitor can step into and vote on which current issues are important to them. Both of these interactives reinforce the purpose of the exhibit which is to look at the passage of the 19th Amendment and the establishment of voting rights for women.

Docents can be found in the exhibit when they have special events open to the public such as family days. They interact with the public by providing a variety of hands on activities that look to teach visitors to the exhibit about the women’s suffrage movement, the 19th Amendment, and the process of an amendment becoming law.

The one change I would make to the physical exhibit is to reorganize the lay out of the last section of the exhibit. In this part of the exhibit, it is not as clear which way the visitor is suppose to navigate. There is the possibility that the visitor could exit the exhibit before seeing the last section. I would redo the design so that the user had to go through the last section before exiting the exhibit.

Digital Presence:

The website for the exhibit, makes the argument that American women gaining the right to vote through the 19th Amendment was not a singular event or process. Instead, it involved the hard work and dedication of countless individuals over several decades. The design of the website reflects this argument by including several different topics and sections that the user can explore. The website allows the users to critically analyze and interpret the primary source documents that are used in the exhibit to tell the story of the 19th Amendment.

The primary audience of this website is the same as those that would go to see the physical exhibit, the general public. The website is designed to provide an overview and highlight key features of the exhibit for potential visitors to the museum. There are a variety of different resources on the website that appeal to a wide-ranging age group. In addition to being able to just explore the documents and artifacts that make up the exhibit, there are also lesson plans and activities that teachers can use in the classroom to teach their students about the 19th Amendment and women’s suffrage. The exhibit website makes the assumption that visitors on the website have no prior knowledge of the topics presented in the exhibit and provide detailed descriptions and background information on the 19th Amendment and the women’s suffrage movement.

The site is laid out with a main page that has the basic details of the exhibit. From this page the user can proceed to a variety of different pages that allow the user to interact with the content of the exhibit in a variety of different ways. The website can be a bit confusing to navigate. The user has to spend a bit of time searching through the different pages to find exactly what is on them and to find what they are looking for about the exhibit. There is not one single way to navigate the website. The user on website can move through a variety of different sections about the exhibit in any order they want.

The exhibit website allows the user to view the online exhibit and examine the primary source documents in each section, watch an introduction video about the exhibit, browse the featured documents of the exhibit, and to find related resources to the exhibit. The main difference between the online content and the physical exhibit, is that online the user can examine the primary source documents in much greater detail and the user has a much easier time actually reading the documents themselves online.

The website does allow the user to browse through the online exhibit. In this interactive element, the user is able to examine the primary source documents used in the exhibit and then read the explanatory captions that can be found next to the documents in the physical exhibit. This experience allows the user to examine the documents up close and read them for themselves to gain a greater understanding of the significance of the primary source documents included in the exhibit.

The exhibit website does include an introductory video where the exhibit curator Corinne Porter gives the viewer a brief overview of the exhibit, explaining the concept behind the exhibit, how the exhibit is laid out, and highlighting some of the most important artifacts in the exhibit. By having this video, the user on the website is able to gain a much deeper understanding of the message the exhibit is trying to convey from one of the most crucial individuals involved in the creation of the exhibit.

The one major thing I would change about this digital experience is the way the website is laid out. I would create a layout the included clear tap for the user to click on that indicated what each section of the website is and what the user can find in that section. I would also include at least a few of the videos found in the physical exhibit on the website. This would provide the visitor online, who cannot come to the physical museum, with as close to an in-person experience as possible.

My name is Andrew Hutsko (you can call me Drew) and I am excited to be a student in HIST 694 Digital Public History this semester. I am taking this course as part of the masters program. I am pursuing a Master of Arts in Applied History with New Media

and Information Technology Emphasis and a specialization in the United States. In addition, I am also pursuing the graduate certificate in Digital Public Humanities. I already have a Bachelor of Arts in History and a Minor in Political Science from American University, that I received in May 2019.

Last semester I took the course An Introduction to Digital Humanities, where I gained background knowledge of the concepts and tools used in the field of digital humanities. As part of the class, I created by own digital humanities project were I mapped around one hundred Carpatho-Rusyn villages in Slovakia and analyzed the relationships between the different villages.

Public history has long been an area of interest to me. Engaging and educating the public about the past is something that I am passionate about. I have always enjoyed talking to members of the public about history and historical events and getting them excited and interested in history. In the world we live today where we cannot have in person interactions with other people, there is a need to use available digital technology to have these same kind of interactions to get the public interested and engaged in the study of history.

My learning goals for this semester are to gain knowledge of an area of the historical field that I have not previously done work in, and to learn how to use different digital technologies to create works of public history.

My digital humanities project consisted of mapping the Carpatho-Rusyn villages in Slovakia to discover more information and find common trends between the different villages.

Aim: The aim of my project was to examine the location of the villages in what is today Slovakia, where the Carpatho-Rusyns have historically lived for centuries, and where they continue to live today. I chose this particular focus because of the personal connection I have with the topic. My paternal grandfather’s ancestors were Carpatho-Rusyns and came to the United States from three of the villages that I looked at. I did narrow the focus of my project as I began to gather the data on the villages. Originally I was planning to look at all of the villages in what are today the countries of Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. I found that there are over six hundred Carpatho-Rusyn villages located across these three countries. I decided to select around one hundred villages from Slovakia for two reasons. First I have a personal connection to the villages in Slovakia as that is where my ancestors came from, and second selected one hundred villages would be much more manageable for this project than looking at over six hundred different villages. I want to not only find out more about the specific villages that my ancestors came from, and also discover some common trends between the different villages.

Sources and Software: The sources I used for my project were two lists of Carpatho-Rusyn villages compiled by Carpatho-Rusyn Knowledge Base and The Carpathian Connection, two websites that provide resources and support for individuals doing research on the Carpatho-Rusyn people. The software that I used for completeing the project was Microsoft Excel and Kepler.gl. I decided that the best way to compare the different villages was through creating a data sheet in Microsoft Excel and uploading it to the mapping software Kepler.gl. I choose Kepler.gl because it allows for the creation of a variety of different map types that can analyze relationships contained in the different categories that my data set contained, and using mapping software made sense since my data concerned villages with fixed geographic points.

Problems: Throughout the process of working on my project, there were a number of issues that I had to address. The first issue I confronted was having to narrow the focus of my project. I quickly decided to narrow my focus from looking at all of the Carpatho-Rusyn villages in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, to just looking at the villages in what is today Slovakia. The main reason that I decided to narrow my focus was practicality. Unfortunately I did not have enough time to gather the data on all six hundred villages into one data set, so I decided to focus instead on a much more manageable data set of one hundred and six villages located in what is today Slovakia. The other problems I had with completing my project came when I was creating the maps in Kepler.gl. I wanted to create two maps that visualized the locations of the former counties in the Kingdom of Hungary and the current districts of Slovakia. I ended up discovering that the best way to display this data on maps was to go into the label feature and selected Historical County in the Kingdom of Hungary and Current District of Slovakia to display this data. The other major problem I encountered in using Kepler.gl was creating the time map. This ultimately proved to be the most difficult part of the project. I wanted to create a time map of when the villages were founded or first mentioned in written sources. When I first went to create a time map by adding the filter I found that it would not display the time graph on the map. After trying to create the time map multiple times, I went back and looked at the data sheet we used when mapping the WPA Slave Narrative interviews in Alabama. After looking at this data sheet I came to the realization that I did not have the dates in my data sheet in the correct format. I could not create a time map in Kepler.gl with just a year, I needed to include a month, date, and time for the founding dates of each villages. After going through my data sheet and adding a date of 01-01 and a time of T00:00:00Z I was able to finally create a time map that displayed when the villages were established or first mentioned in written sources.

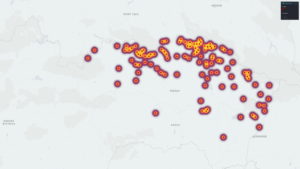

Discoveries from Sources: There were a few different facts that I discovered about my sources from creating maps in Kepler.gl. From the five maps I created for my project, I was able to learn a few different things about the one hundred and six Carpatho-Rusyn villages that I examined. First, I discovered that the villages were scattered across the entire Prešov region of Slovakia, and a few of the villages were found in the northern Košice region. Second, I found that the highest density of villages could actually be found in the northern Prešov region close to the Slovak-Polish boarder. Next, the time map I created revealed that the period between 1397 and 1422 saw the largest amount of villages either being established or first mentioned in written sources. Finally, I discovered that the largest amount of villages were located in the historic Hungarian counties of Saros and Zemplen and the current Slovak districts of Stará Ľubovňa, Svidník, and Bardejov.

Project URL: http://andrewhutsko.org/uncategorized/carpatho-rusyn-villages-in-slovakia/

For my project, I wanted to find out more information about the villages where the Carpatho-Rusyn people have historically lived in Europe. The Carpatho-Rusyns are an East Slavic ethnic group that have lived for centuries in and around the Carpathian Mountains in what is today Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. There are estimated to be around six hundred villages that make up the core of historic Carpatho-Rusyn settlement which means that fifty percent or more of the population identified as Carpatho-Rusyn.

This project came about as a result of my personal family research which I have conducted over the past year. I discovered that my paternal grandfather’s ancestors were Carpatho-Rusyns from what is today Slovakia, who immigrated to the United States. My desire to learn more about my own family led me to want to research the villages my ancestors were from. My goal was to find out what kind of relationships I could find between the different villages looking at a variety of different facts about the villages, and create a project that could be shared with other people who have Carpatho-Rusyn ancestry interested in learning about where their ancestors were from.

I decided that the best way to compare the different villages was through creating a data sheet in Microsoft Excel and uploading it to the mapping software Kepler.gl. I choose Kepler.gl because it allows for the creation of a variety of different map types that can analyze relationships contained in the different categories that my data set contained, and using mapping software made sense since my data concerned villages with fixed geographic points.

One of the first decisions I made was to narrow my focus to only one hundred and six villages found in the Prešov region of northeast Slovakia. I choose to focus on these villages as it was a much more manageable amount of data to work with rather than looking at all of the six hundred Carptho-Rusyn villages in Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. I specifically choose this region of Slovakia because that is where my ancestors are from and I have a personal connection to three of the villages there.

Once I decided which villages I wanted to include, I next created categories for my data sheet about each of the different villages. The categories that I decided to include were the name of the village in Rusyn, the name of the village in Slovak, the name of the village in Hungarian, the year that the village was either established or was first mentioned in written sources, the historical county in the Kingdom of Hungary where the village was located, the current district of Slovakia where the village is located, and the latitude and longitude of the village. I obtained all of the information about the different villages from the Carpatho-Rusyn Knowledge Base and The Carpathian Connection (both of which I have provided links to at the end of the post).

Once all of the data was compiled into the spread sheet, I uploaded it to Kepler.gl and created five different maps with the software to analyze different relationships contained in the data. From these five maps I was able to learn a few different things about the one hundred and six Carpatho-Rusyn villages that I examined. First, I discovered that the villages were scattered across the entire Prešov region of Slovakia, and a few of the villages were found in the northern Košice region. Second, I found that the highest density of villages could actually be found in the northern Prešov region close to the Slovak-Polish boarder. Next, the time map I created revealed that the period between 1397 and 1422 saw the largest amount of villages either being established or first mentioned in written sources. Finally, I discovered that the largest amount of villages were located in the historic Hungarian counties of Saros and Zemplen and the current Slovak districts of Stará Ľubovňa, Svidník, and Bardejov.

This project is one that I would like to expand upon in the future. I see this project as a starting point for learning more about the Carpatho-Rusyn villages in Europe. I would like to eventually expand my data sheet to include all of the Carpatho-Rusyn villages in Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. With this expanded data set I will create new maps to be able to analyze the relationship between all of the over six hundred villages.

Carpatho-Rusyn villages point map

Carpatho-Rusyn villages heat map

Carpatho-Rusyn villages time map

Carpatho-Rusyn villages in Historic Hungarian Counties

Carpatho-Rusyn villages in Current Slovak Districts

Carpatho-Rusyn Villages in Slovakia: Data Set

Links for village data:

http://www.carpatho-rusyn.org/villages.htm

https://www.tccweb.org/carpathorusynvillages.htm